Editor’s note: Michael Caggiano is a longtime Fire Learning Network partner and Fire Management Specialist with the USDA Forest Service. Ty Aldworth is a Research Associate with the Colorado Forest Restoration Institute. In this blog, they share lessons learned from six 2023 fires in Southwest Colorado.

This blog is the second in a special 2024 series on “managed wildfire.” All wildfires are managed somehow. There is increasing interest in and action around doing so in a way that prioritizes safety while also considering how to use wildfires to achieve burned acres in ecosystems where it is appropriate. This blog series will explore the stories of practitioners who are finding ways to safely and creatively manage wildfires in their place. Stay tuned for future posts on this theme.

Smokey Bear was officially born soon after rangers pulled a young cub from the ashes of a smoldering wildfire on the Lincoln National Forest in New Mexico. For decades, he has been preaching that “Only YOU can prevent wildfires,” propagating the war on fire and the belief that we can eliminate fire from the landscape. That is slowly changing. A more recent post from the Lincoln National Forest, “Fire will save the forest” underscores that change by highlighting the importance of reintroducing fire and spotlighting Indigenous burning practices and perspectives. This is illustrative of a sea change in how we as a fire community are beginning to approach fire on the landscape. Managers, like those highlighted below, are increasingly recognizing that wildfire cannot and should not simply be removed from an ecosystem. The simple fact is the more we suppress small fires, the more devastating later fires become. This seeming contradiction, known as the wildfire paradox, is an undeniable reality we face. It hints at a larger truth: the path to thriving with fire actually requires accepting more of it.

Setting the Stage

Over the last decade plus, managers in Southwest Colorado have embraced this truth. Recognizing the challenge, they have invested heavily in community engagement and strategic fire planning. The San Juan National Forest has worked with community forestry collaboratives to plan wildfire mitigation efforts and also developed Potential Operational Delineations (PODs) to identify the most effective control features throughout their landscape (more information and examples here and here). PODs incorporate local knowledge and advanced spatial analytics to predict where firefighters can most effectively and safely hold a fire – irrespective of ownership or jurisdiction. Managers integrated PODs with stakeholder engagement, prescribed fire planning, fuel treatment prioritization, and external communications to set themselves up for success when opportunity arose.

Examples from Six Colorado Fires

In summer 2023, six lightning fires tested how local managers near Pagosa Springs, CO would take advantage of those opportunities. During these incidents, managers and local stakeholders were, at times, able to leverage their planning and manage wildfires to effectively reduce long term risk. However, they sometimes found themselves falling back into old habits. Local managers wanted to share their experience and produced a series of short videos describing how their thinking and response are evolving to respond to wildfires more proactively. The videos champion their successes while also laying bare their challenges.

See the video series here – “An evolution of thinking”

Chris Mountain:

The first of the six fires was detected just west of Pagosa Springs in late June. Although conditions were similar to local prescribed fire burn windows, agency decision-makers struggled to provide clear leaders’ intent to incident management teams (IMTs) and the public regarding a management strategy at the fire’s outset. With this uncertainty, firefighters defaulted to immediate, direct suppression. At its peak, the fire was staffed by 563 people, and by the time the fire was fully contained at 511 acres, it had cost $8.6 million.

Dry Lake:

The second fire ignited in late July in a prescribed burn unit already prepped to be lit that fall, which was also a designated POD. The control features previously identified in the PODs process and prescribed burn plan presented an opportunity to execute a strategy other than immediate suppression. Assessing local fire danger, weather data, and utilizing Risk Management Assistance (RMA) analytical tools, the Forest developed a plan to bring the fire out to the prescribed fire unit/POD boundary. The local team conducted a structured risk-based conversation using the Incident Strategic Alignment Process (ISAP) framework, where agency administrators and local stakeholders collaboratively evaluated critical values at risk, developed strategic actions, documented risks to responders, and determined the probability of success. Under conditions similar to the Chris Mountain Fire, managers used the Dry Lake ignition to re-introduce ecologically appropriate fire. Though the Dry Lake Fire was twice the acreage of Chris Mountain, the strategy allowed managers to staff it with 75% fewer people at 20% of the cost.

Bear Creek, Quartz Ridge, and Mosca:

The Bear Creek Fire was detected in early August north of Pagosa Springs. Managers recognized this fire was in a risky area with snags and rugged terrain. After several days initial direct suppression actions proved futile. Concurrently, two more remote ignitions were detected – the Quartz Ridge and Mosca Fires. Together, this prompted the Forest to reconsider their direct suppression posture. Similar to Dry Lake, the Forest decided to consider and evaluate each fire through structured risk-based strategic dialogues using ISAP, and once again leveraged RMA and other advanced analytics to consider their options. On Quartz Ridge and Bear Creek, the dialogues and analytics enforced what decision-makers had felt all along – there were few values at risk and no great suppression options. However, reconsidering direct suppression of the Mosca Fire would allow managers more space to utilize indirect strategies on Quartz Ridge and Bear Creek. They invited the Pike Hotshots into their ISAP discussions to collaboratively discuss the risks associated with different strategies. The decision was made together to go direct on Mosca, and that fire was suppressed at seven acres. Putting Mosca to bed allowed the Forest to manage the Quartz Ridge and Bear Creek Fires more effectively for several more months until a Thanksgiving snowstorm naturally extinguished them.

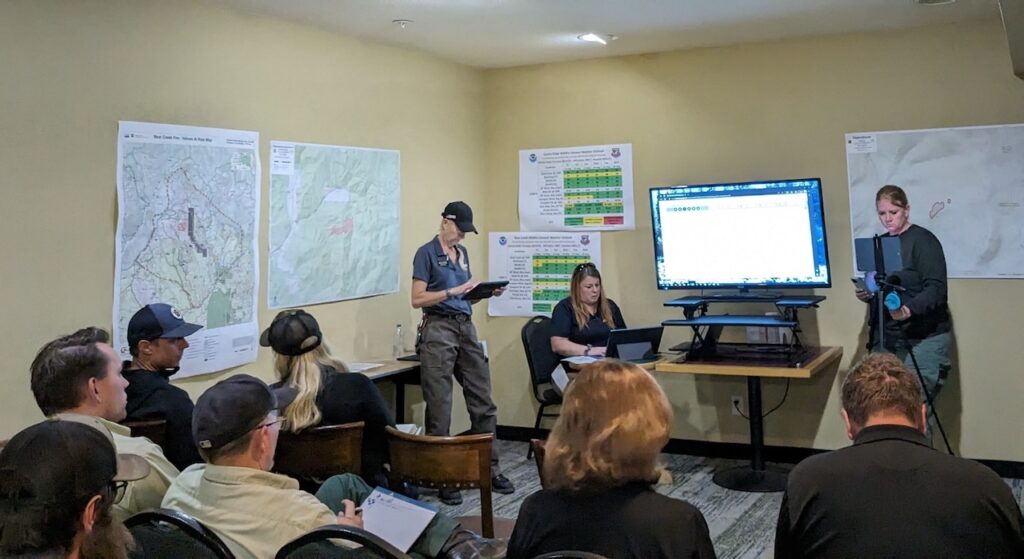

During the Bear Creek, Quartz Ridge, and Mosca fires, agency administrators partnered with the IMT to hold meetings with cooperators and local forest collaborative groups. In these meetings, both parties transparently discussed their decision-making process and connected directly with the local community to build social capital. These meetings with collaboratives and interested stakeholders, which actually started years before, helped pull back the curtain on fire management decision-making and strengthened a two-way dialogue between land managers and local stakeholders about how they can share wildfire risk and responsibility.

Trail Springs:

The final incident started in mid-October near the Chris Mountain footprint. Most resources and managers were already weary from a long season. However, increasing fire behavior made it unsafe to engage directly and suppress this fire quickly. In a twist of fate, this new fire was so close to the Chris Mountain footprint that the landscape it impacted likely would have burned during that previous incident if managers had utilized more indirect tactics. Again, the Forest used the ISAP process to develop, evaluate, and transparently communicate their strategy. Through these dialogues, they were able to articulate and balance critical values at risk with potential firefighter exposure. Agency administrators and the IMT committed firefighting resources deliberately in places where they felt they would be successful. The fire was successfully held, and along one edge, the Chris Mountain perimeter was utilized as a holding feature.

Key Lessons Learned

Identify windows of opportunity: Fuel and weather conditions and resource availability are dynamic. Thinking outside the box can help realize opportunities to manage wildfire differently. Additionally, this year’s large incident can be used as the next fire’s best holding feature – as demonstrated during Trail Springs. Incorporating new disturbances into pre-response planning can help maximize their potential as holding features.

Provide clear leader’s intent: Without clear intent from agency administrators, firefighters and IMTs default to their experience and often suppress fires at the smallest possible size and earliest possible opportunity. Clear intent is required to consistently execute an alternative approach, and ensure we leverage our highly skilled fire workforce in pursuit of strategies that will more effectively reduce long-term ecosystem, community and firefighter risk.

Invest in stakeholder engagement: Working with partners and local collaboratives well before a fire starts is imperative to fostering a sense of shared responsibility. Ongoing communication and dialogue with stakeholders before, during, and after fires is critical to a successful, long-term fire management strategy. These efforts build social capital to better support complex decisions both now and in the future.

Leverage analytics and facilitate risk-based dialogues: Using analytics to facilitate strategic, risk-informed, and transparent dialogues can improve alignment between incident leadership, land managers and firefighters on the ground, resulting in higher quality decisions and increased trust.

Be prepared: Facilitating and participating in collaborative pre-season strategic planning efforts, such as Potential Operational Delineations (PODs), can help prepare a landscape to manage fires more proactively by creating a common operating picture and institutionalizing local fire knowledge. Additionally, actively preparing for long-duration events, anticipating, and mitigating late-season workforce fatigue, and building local fire management programs with the needed skill sets to manage long-duration fires can help develop local capacity and evolve the fire management paradigm.

Communicate the “why”: Good decisions may come with considerable institutional and personal risk, but with thoughtful, inclusive, and transparent processes risks can be considered more holistically. Understanding the “why” behind decisions provides critical context and can help create alignment between land managers, incident teams, firefighters, and the local community.

Conclusion

These fires and lessons, taken together, contribute to a developing robust and resilient strategy for Southwest Colorado that considers both ecological and social risks. It is impossible to live in fire-adapted ecosystems without fire. It is also true that managing wildfire more proactively comes with its own set of risks that must be navigated with nuanced decision-making. However, the choice is clear. Managers in Southwest Colorado recognize that fire is inevitable. They’ve decided it’s better to take advantage of fires when conditions favor control than to take their chances when they don’t.

Though fire managers in these examples sometimes fell back on old habits, their self-reflection and willingness to learn and improve demonstrates an admirable fire-forward philosophy. We can all strive to be more thoughtful in our approach, develop strategies, transparently discuss decisions, and slowly shift the fire management paradigm toward a sustainable co-existence with fire. Only fire will save the forest. Let’s give it that chance.

****