Editor’s note: Max Nielsen-Pincus and Cody Evers join us for this guest blog post from the Department of Environmental Science and Management at Portland State University. In this blog, they share six lessons they gained from studying a sample of networks in the Western US working to reduce community wildfire risk.

It is a common refrain to hear calls for more defensible space, increased fuels management, new building codes, improvements in emergency response, or strategies for wildfire recovery. Unlike suppression, where a clear command structure dictates objectives and lines of authority among partnering agencies, no formal command structure exists for community adaptation and mitigation. Rather, communities of fire adaptation and mitigation practitioners are attempting to improve fire outcomes by using their power as a system of connected entities – as networks – to influence each other, those who they serve, and the systems they work in. As a result, communities across the country have developed unique strategies to address wildfire risk that involve landowners and residents, local government, state and federal agencies, non-profit organizations, and the private sector. These mitigation and adaptation efforts play out across a wide array of jurisdictions and land ownerships. To emerge and thrive, community networks must facilitate coordination and action among actors.

Between 2018 and 2022, we studied community wildfire risk reduction networks in Central Oregon, North Central Washington, Northern Utah, and Northwestern Wyoming, four of several dozen regional hotspots of wildfire risk found in the Western US. Although few of these areas called their connections a formal “network, they worked in network ways – leveraging their connections and working across sector and geographic boundaries. Our goal has been to learn from these networks to better understand how their structure and function influence the pace and scale of wildfire risk adaptation and mitigation. One of the key takeaways from our research is that networks and network thinking play a critical organizing function – allowing local parties to influence one-another and to extend their impacts beyond the local context. By sharing what we have learned we hope practitioners will be able to develop effective networked strategies to advance wildfire risk reduction in other wildfire-prone locations.

Hotspots of wildfire risk in the western US (including the 4 we report on circled in bold) are also hotbeds of local innovation built from decades of working partnerships that form the social infrastructure that makes proactive management of wildfire risk possible.

Lesson 1: Developing a flexible, but galvanizing set of local stories about wildfire acts as a cultural catalyst and connection point for a variety of actors to engage in wildfire issues.

As Winston Churchill once remarked: “Never let a good crisis go to waste.” In each of the areas we studied, we found a story of a catalyzing event or set of events that served two key purposes: 1) the events allowed practitioners to develop relationships with each other, and 2) the stories gave each actor a way to orient their work in relationship to local fire. While each of the narratives referenced fires, some recent and some from decades past, each narrative focused on social responses and organizing as a means of developing more fire-adapted and defensible communities. For example, many practitioners in North Central Washington cited the 2014 and 2015 Okanogan and Carlton Complex fires as points of both trauma and leverage that helped grow the Washington Fire Adapted Communities Network and the emergence of community coalitions and community-based organizations working to stitch together the aims and actions of otherwise siloed agencies and organizations.

Neighborhoods, communities, and regions can develop their local narratives based on what makes sense for them. Catalyzing events are a common starting point for these narratives, but the end points are as diverse as the places from which they originate. And although the narratives may mask the actions, relationships, and efforts that occurred before the catalyzing event, they can also reinforce past relationships and actions, and reenergize community, state, and federal efforts to mitigate risks and improve preparedness.

Wildfire provides the catalytic event that spurs new efforts to address wildfire risk proactively even as the exact meaning of those events means different things to different people. Credit: Karina Branson at ConverSketch.

Lesson 2: Coordination is key, but not everyone needs to be a coordinator or play the same role. People wear multiple hats; the hats worn are often specific to individual relationships, and these hats are only loosely associated with a specific job title or organizational affiliation.

In our four study sites, we identified over 1,600 people who manage wildfire risk as a focus for their work. While the number of participants in our community networks is a conservative estimate at best, the array of authorities, jurisdictions, roles, and interests involved and the patterns of relationships among them are impressive. These people were experienced – a majority reported working in wildfire for over 10 years, represented hundreds of organizations – federal and state agencies, local and tribal governments, fire response organizations, non-profits, community groups, and private sector businesses – and played many roles, acting as jurisdictional authorities, facilitating planning, engaging community members, assessing risk, and implementing risk reduction projects.

At the end of a workshop in North Central Washington, participants coalesced around the need for increased resources focused on coordination as one of two main goals for their future. Coordination, they argued, is a critical role that enables resources to be leveraged strategically creating efficiencies instead of competition, but requires resources to connect and maintain relationships between otherwise disconnected actors. A coordinator with the appropriate training, professional support, and local knowledge and relationships can provide a critical foundation to expand community networks for wildfire risk management. We saw a version of this strategy employed in Utah where state legislation created WUI coordinator positions intended to span the many boundaries between land ownerships, organizations, and jurisdictions in the Wasatch Region. Coordinators help maintain relations among individuals and organizations, and with leadership to make space for perspectives that may be perceived at odds with the goals of those already engaged, coordination can help expand the scope of who is involved. Leadership, in this context, is not just about having the right technical acumen for mitigation and wildfire risk reduction, it’s about being a good social fit, building a story that remains inclusive and responsive to the needs of partners, and identifying individuals with whom they can build bridges across what may initially appear as a wide divide. These characteristics increase the likelihood that those who hold them build trust and influence with those they tack back and forth between – the underrepresented and those at the center.

Lesson 3: Coordination looks different across locations, but boundary spanning is one common thread – and critical role – across the study areas. Deliberately building connections with people who are positioned and able to reach across sectors or scales increases the mobility of your network.

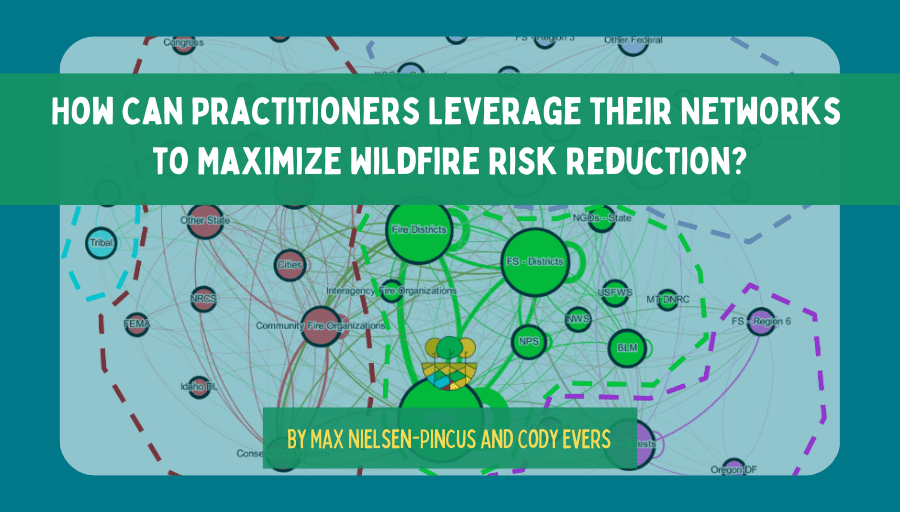

Approximately 95% of survey participants in each study area reported that collaboration was an important part of their job or their organization’s mission. Despite broad agreement on the importance of collaboration, it is clear when looking at the structure of working relationships that a few specific individuals emerge as important boundary spanners. Boundary spanners are individuals that help connect and facilitate interactions among local, state, and federal actors. Exactly who these individuals are, their titles and their affiliations varied drastically by region. In North Central Washington, NGOs supported by the Washington Fire Adapted Communities Network played an important role in connecting federal, state, and local interests. In Northern Utah, Utah DNR’s Division of Forestry, Fire, and State Lands WUI coordinators often played a key role in engaging local communities and connecting them to state and federal resources and initiatives. Local government initiatives in Central Oregon, like Deschutes County’s Project Wildfire, filled gaps between communities and higher-level agencies, while in northwestern Wyoming, boundary spanning staff from local fire departments, the US Forest Service, and conservation districts have partnered together in place-based coalitions like the Teton Area Wildfire Protection Coalition. These roles emerged over decades in some cases and the factors that precipitated the emergence of boundary spanning (including individual leadership, purposeful collaboration, serendipity, and targeted investments) are unique to each region.

Organizations, agencies, and stakeholders involved in Washington’s wildfire risk management network show clusters of practice that require coordinating work across landscape and organizational boundaries.

Lesson 4: Trust allows practitioners and stakeholders working in wildfire risk management to build common ground and influence each other. Consider how to build trust and understanding among stakeholders so that the stories you share – and the work that you do to reduce wildfire risk – better reflects and includes the whole community.

Trust is the currency of collaboration. A lack of trust limits belief in the character, reliability, and security of a relationship. In contrast, a trusted friend or colleague is someone you can depend on, believe in, and even advocate for.

In our research, the most well-connected individuals in each network were the most likely to be rated as major influences on survey participants’ work. Well-connected individuals span boundaries between organizations at the local, state, and federal levels, and build the trust required to influence both practitioners and stakeholders, and the larger system those individuals work in.

This finding transfers to the organizational level as well. Survey participants in Central Oregon, North Central Washington, and Northern Utah reported high trust in organizations that were best represented in community networks, and less trust in those who were less represented in the networks. Although the specific organizations that were most trusted varied across the four regions (and included state, federal, and local organizations), trust was strongly correlated to the perceived differences in organizational missions and goals.

Lesson 5: Networks change. Like any living system, local fire management networks will grow, retract and respond to the conditions they exist in. Deliberate efforts on the part of people who have been working on fire issues in place over time is needed to weave newer actors into local networks and partnerships.

Social capital is built through trust, repeated interactions, and a shared sense of collective action. Investments in social capital form the platform on which future projects are planned, implemented, and evaluated.

Turnover was a common lament in all of the regions we studied. Across our study areas, roughly 1 in 7 respondents indicated that they were unlikely to continue working on wildfire issues in their regions in the next 5 years. Turnover is the result of professional development, organizational culture, demographic change, and burnout. For example, the shifting landscape of federal staff and line officers can leave collaborative efforts without a stable face at the table, limiting trust that one participant’s word will be maintained by the next.

We also heard about burnout. In all of our study areas, participants talked about colleagues who burnt out or left their position owing to stress, poor pay, or hitting the end of their rope. While combating turnover is beyond the scope of our research, practitioners in community networks can help each other. During a virtual workshop in Central Oregon, one participant described the challenge of being new to the region and their position, including connecting with people outside their organization, learning the local narratives of wildfire risk management, and building partnerships that offer credibility to their efforts. Workshop participants agreed that they could make more deliberate efforts to share their trusted narrative and integrate new actors into the region’s boundary-spanning wildfire risk work.

Lesson 6: Don’t let implementation pressure narrow your view of the issues, determine who should/could be involved, or drive toward inequitable outcomes.

Building relationships requires purpose, investments, and time. There is no guarantee that outreach will be fruitful, that new members will click, or that interests align. Think of these uncertainties as the cost of spanning boundaries. These costs increase the price of mitigation and adaptation measures and limit where and with whom community wildfire risk management networks work. We heard from practitioners in each of our study regions who faced the dilemma between working with tried and true partners and reaching out to expand the scope of who is involved in wildfire risk reduction. Often the answer was to go with existing relationships, especially given that most mitigation programs limit funds to fuel treatments and infrastructure investments. Rather than giving into demands that reify inequitable outcomes, identify strategies to build social capital equitably. If you have authority over mitigation and adaptation programs, how can your resources be used to support the scaffolding of coordination and relationship building? An ounce of coordination may be worth a pound of mitigation.

This issue was highlighted in a workshop in Oregon where participants talked about the flood of state and federal funding that followed the passage of new legislation. While expressing gratitude for the resources, those same practitioners expressed frustration with the funding and time constraints imposed by the newly appropriated resources. As one participant put it, federal and state resource abundance often means “pointing the ‘money cannon’ at shovel-ready projects.” Consider how thinking like a network can help prepare for doing the right things in the right places at the right time with the right people rather than allowing funding silos to result in action that focuses narrowly on low-hanging fruit.

Local connections shape fire outcomes.

Our findings paint a picture of relatively well-developed and well-connected networks of organizations and actors working together to reduce wildfire risk in multiple different wildfire hotspots of the western US. We view these networks as a foundation on which communities are attempting to mitigate and adapt to the changing landscape of risk. Regardless of the wildfire hotspot, unique place-based initiatives have a vital role to play to connect local goals and place-based knowledge with broader federal and state aims. Initiatives like Deschutes County’s Project Wildfire, the Teton Area Wildfire Protection Coalition, and the many others we heard about may be the foundation of the American initiative to adapt to wildfire, sparking innovation and stitching together a network of actors to act in coordination towards the common good.

Methods and Acknowledgements

Our studies of community wildfire risk networks began in 2018 and have continued since. Our work in each region has been slightly different as we’ve experimented with different approaches to connect to and map out the relationships among practitioners and stakeholders at all levels in each region and adapt to the changing conditions of the pandemic. More information about the research can be found at: https://sites.google.com/a/pdx.edu/maxnp/research/Wildfire.

We are grateful for the contributions of Derric Jacobs, Matt Bauer, Hannah Spencer, Liam Resener, Christian Heisler, and a handful of other undergraduate and graduate students at Portland State University who had a hand in research design, data collection, and survey recruitment. Dan Williams (US Forest Service), Bart Johnson (University of Oregon), Brett Miller (University of Montana), and the staff of the Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network have been instrumental in shaping and supporting our work. We are indebted to the over 1,000 people who participated in surveys, workshops, and interviews: Without your help, this work would not have been possible. We are also grateful to the US Forest Service’s Rocky Mountain Research Station and the National Science Foundation for their financial support.

####

Max and Cody, you may have concentrated only in certain areas of the West, but your descriptions certainly resonate with me here in Lake County, California. Your introduction of the term “boundary spanners” reminded me of a FAC Net blog article on netweaving fits in rather well with the Western orientation towards tools rather than processes and could be more useful as a result. Have you published some form of this article as a paper somewhere?