Photo credit: Autumn is a perfect time to delve into a good book. Photo by Canva Creative Commons.

Author’s note: I am extremely grateful to Dr. Sarah Ray, and to all of the book club participants, for sharing their time, attention and insights. The opportunity to learn together, at a time when the value of connections and personal resilience cannot be overstated, was a gift. In the words of one of our participants, “This book was exactly what I needed right now.”

If you are inspired by the idea of learning with other fire adaptation peers, you can join FAC Net as an Affiliate member to access book clubs and other peer learning opportunities.

If 2020 has been serving you, like it has me, lesson after lesson along the lines of a neon sign in the sky reading:

Then I have some autumn reading to recommend.

Recently, I was double-booked in Zoom meetings (sound familiar?). I chose to tune into a conversation hosted by my friend and colleague, Lenya Quinn-Davidson, with Dr. Sarah Ray, author of the recently released, “A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety”. Listening to their conversation, I thought about how FAC Net staff had been considering launching a book club

Cover of Dr. Sarah Ray’s Book. Photo courtesy of Amazon.

(inspired by partners in Montana). Once I read Lenya’s blog post about Dr. Ray’s book I knew this was exactly the right book for our book club. A couple of weeks later, Dr. Ray had graciously agreed to participate and FAC Net’s first book club offering officially kicked off.

Our vision for the book club was to create an additional pathway for peer learning, connection and skill building. We wanted the book club selection to support people working to improve community resilience and fire outcomes by exploring themes that are “fire adjacent.” Meaning themes focused on resilience, connection to place and culture change without being too obviously all about fire. Dr. Ray’s book, with its focus on practitioner self-care in the face of an intractable, complex and wicked problem, was perfect.

We ran the book club in two sessions. The first session used small groups to explore peer insights and connections between the book and our work as fire adaptation practitioners. The second session was a conversation with the author. What follows are some of the highlights from those conversations and major themes from the book.

Your COVID-19 anxiety is climate anxiety. And your fire work can be part of a coalition of larger social movements that seek a better future.

In the introduction to the book Dr. Ray recounts her realization that her job as an environmental studies professor was not to “dazzle {students} with the extent, scale and scope of interconnected problems” (p. 11). She began questioning the outcomes of an approach based on the premise, “when audiences can see the problems of the world they’ll be more likely to go out and try to fix them.”

I see this same framework engrained in the ways we’ve learned to think and talk about our fire problems. Seeing our fire problems is rarely enough to create the conditions we need to fix them. Like Dr. Ray, fire adaptation practitioners have to recognize the limitations of this thinking or risk lonely self-righteousness, and even worse, inefficacy. This recognition does not require us to abandon the expansive and interwoven nature of the systems transformations we seek, but rather, to build some new skills to bring to that work—skills that help us sit in tension and that sustain our ability to engage.

Dr. Ray’s book was published right before the COVID-19 pandemic and surge in social justice activism. Both have helped to crystalize how many of dominate society’s systems are frayed and unjust. For many people used to the privilege of food security, early disruptions to supply chains were a shocking reminder that these systems are not infallible (or equitable). And while seeing empty grocery store shelves was confronting, the outsized impacts COVID-19 has had on Black, Indigenous and people of color in the US, whose infection and death rates far exceed those of whites, should bring into focus the imperative to address social justice if we hope to make headway on any of these interconnected issues.

In the conversation with Dr. Ray, we probed the overlaps between public health, social justice and climate. Dr. Ray noted the phrase, “I can’t breathe,” is both about police violence on Black bodies and environmental justice, whose leaders have repeatedly said, “tell me your zip code and I can tell you your health outcomes.” Smog, air pollution, environmental health disparities and even the impacts of wildfire all disproportionately impact people of color.

So where does this leave us? With even bigger problems than we imagined? Maybe. But this book, and the source material it references, offers a road map out of “the overwhelm” and toward something the book calls upon us to create: a vision for a better future. One we want to live in. One where “radical imagination” is our most precious asset.

The myth (and maladies) of individualism

One of the book club participants shared that the most powerful idea in this book for them was the concept that we don’t have to try to do everything ourselves, or all at once. They said this recognition offered “better perspective and freedom.” So many of us in fire are driven by a narrative of urgency. The next fire season is always around the corner. We’ve worn that urgency as a badge of righteousness and (wrongly) assumed it would prod the public into action. But we haven’t always examined the implications to ourselves or our society of defining this work in terms of an urgent life and death crisis…and the way that places us in a position to “save” our neighbors.

The book offers a critique of individualism and its friends – self-aggrandizement, savior complex and privilege. Dr. Ray says that the idea of individualism—that we are one person in a tidal wave—is one of the top barriers folks face when entering this work.

Are the twin narratives of urgency and individualism propelling fire adaptation practitioners to act without strategy? Are they positioning us alone on a hill in an unwinnable war? Alone to face the psychological consequences when the actions of one are inevitably insufficient to protect the many? What are the alternatives to martyrdom? This book offers options and practices to help identify ways to cultivate “long term stamina” and work from “generosity of spirit” rather than from urgency.

What’s more valuable than gold?

How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives. -Annie Dillard

When asked how she uses the ideas and tools in the book in her own life, Dr. Ray shared that she has been working really hard on “media diet” practices lately. Recognizing that our attention is “like gold” and that media seeks to rob us of as much if it as it can, she intentionally safeguards her attention, treating it as the limited resource it really is.

She goes on to share her surprise in discovering that “community relationships and trust are more valuable than things like infrastructure {in} bouncing back from ecological disaster.” Dr. Ray had spent years teaching and developing her own relationships with students, but not necessarily concerning herself with the connections among them. As she researched and wrote this book, she realized that relationships among students were going to be among the most important investments she could make.

“Here we were going through a disaster (the pandemic) and what were we going to need? Each other. And we had done that work to build relationships, and I was so grateful to have shifted to that focus.”

Honing our ability to recognize value, often in the intangible, is critical to our work as fire adaptation practitioners. Deliberately choosing how to allocate our resources and attention, is how we’ll stay true to the purpose that drives us.

How do we prioritize our time and resources?

Reflecting on our work in fire adaptation, one book club participant lamented, “So much of our time is spent working with the most affluent residents [whose homes in many communities are situated in locations at risk to fire]. How can we engage others in our communities who are more vulnerable in general, but whose homes will be impacted by secondary debris flows or other issues rather than the direct threat in a major fire event?”

How indeed. Perhaps, in part, through reframing.

If you frame the prize as: “stop homes from burning” you will take different actions then if your frame is “how do we create right relationships between people, place and fire?”

So why don’t we just adopt this new frame? In part, because of another issue the book explores: measurement.

Ray suggests that we’d do well to “start with shifting our perception of what an ‘impact’ is, how big it needs to be, and whether any one of us can make enough of it.” (p. 59) She goes on to encourage readers with the knowledge that, “Triumphant moments are the result of the invisible work of scores of unnamed idealists and of forces impossible to track.” (p. 61) And while on the one hand, this is encouraging (the weight of the world is NOT all on my shoulders) the systems we operate in (and much of our funding) is based on tracking specific outputs, leaving practitioners in a conundrum.

Resisting measurement and reframing collective problems are both easier said than done. But if we don’t start talking about how ill-suited to measurement the complex changes we’re seeking are, will we ever have the chance to operate differently?

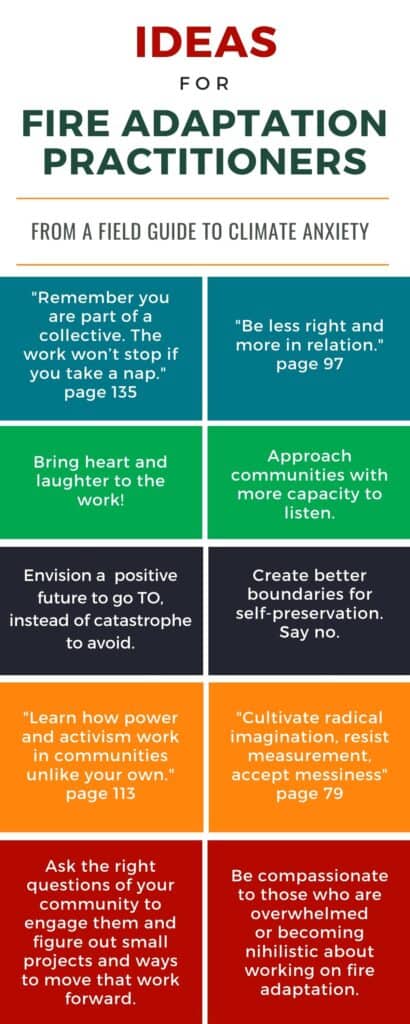

Graphic showcasing our book club’s favorite quotes from Dr. Ray’s book. Graphic courtesy of Michelle Medley-Daniel

How do you reach someone?

Arguably the most popular section of the book in our club, Chapter 5: “Be Less Right and More in Relation,” was full of tips for communicating about any potentially polarizing issue, including fire. One of the book club participants challenged other practitioners, “go back to your partners and ask, who are we trying to reach, what are their values, and how can we reach them?”

Doing the work to understand your audience and to be thoughtful about the language and concepts we use so that we don’t unnecessarily alienate other community members takes work, but local leaders are well positioned to undertake it. It turns out the best thing to change a person’s mind is a peer messenger that they trust. The messenger matters more than anything else. Take stock of your partnerships as one of our book club members suggests. Consider who among you is best positioned to be the messenger for a given audience and don’t be afraid to reframe privilege, activism and climate change, as those can all be non-starters in a conversation. Find the common ground in our conversations—we are all on this planet and in these communities together. Inevitably there are ideas and values that overlap, even in our hyper-polarized world.

Another aspect of this work is examining our motives for and orientation to the engagement. Have we come to save or have we come to labor together as Ray quotes Indigenous organizers, “If you have come to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.” (p. 73)

What is being made “resilient”?

The book offers a salient critique of resilience. “Bouncing back” is a way of resisting change and re-stabilizing existing systems and power dynamics. Consider our Indigenous partners, from whom folks in the fire adaptation world have taken so much inspiration. How must the narrative of resilience sound to people from whom the land has been stolen and their fire practices disrupted or outlawed? Would we really seek to continue the injustices perpetrated on them? When we say we want communities that can “bounce back from fire” what do we really mean? Have we considered, specifically, what we want to bounce back, and what we want to change?

Resilience of our current fire management system requires us to double down on centralization and homogenization. It supports the marginalization of communities and perpetuates injustice. As leaders in fire adaptation, we must ask ourselves, what are we trying to fortify? Who gains from bouncing back to how things were? Who loses? What are our alternatives? How do we recover strategically to be better, more equitable and more just?

Are you an activist?

Participant Takeaways from Book Club Discussions. Chart courtesy of Michelle Medley-Daniel

How do you see yourself and your work? Are you a leader? “The Second National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit redefined leadership as founded in facilitation, community building, and bottom-up organizing.” (p. 65)

Is your fire adaptation work activism, community organizing, power building, self-care, radical imagination?

If any of those are new ideas or frames for your work, I suggest you read this book and tap into a practical set of tools for sustaining yourself and your fire adaptation work.

Please note that comments are manually approved by a website administrator and may take some time to appear.

Interesting article with helpful tips and approaches for improved communications/relationships. However, FACNET hardly seems the place to introduce if not endorse election cycle ‘hot’ words/concepts that are turbulently flowing throughout our already overheated political waters.

From this well-seasoned retiree’s perspective and from my grizzled “veteran” status with various volunteer organizations and campaigns, here’s a quiet suggestion: continue building relationships, coalitions, and partnerships; and maintain clear focus on finding that elusive ‘common ground’ that is so essential in finding common sense, issue resolution. Our world and our lives are convoluted enough. Please keep our “learning network” focused:

To live better with fire, we need to adapt to fire. That’s where the concept of fire adapted communities comes into play. Local people learning and working together is the foundation of fire adaptation. Learning and working together builds community capacity and resilience.

How do you subscribe to the book club and its offerings?