Editor’s Note: FAC Net staff had the opportunity to sit down with Dr. Alessandra Jerolleman and talk about recovery and justice. Alessandra is an Assistant Professor in Jacksonville State University’s Emergency Management Department, as well as a community resilience specialist and applied researcher at the Lowlander Center. Dr. Jerolleman is one of the founders of the Natural Hazard Mitigation Association (NHMA) and served as its Executive Director for its first seven years. Alessandra is a subject matter expert in climate adaptation, hazard mitigation, disaster recovery and resilience with a long history of working in the public, private and nonprofit sectors. Dr. Jerolleman speaks on many topics including: hazard mitigation and climate change; campus planning; threat, hazard and vulnerability assessments; hazard mitigation planning; protecting children in disasters; justice in disaster recovery; and public/private partnerships.

Editor’s Note: FAC Net staff had the opportunity to sit down with Dr. Alessandra Jerolleman and talk about recovery and justice. Alessandra is an Assistant Professor in Jacksonville State University’s Emergency Management Department, as well as a community resilience specialist and applied researcher at the Lowlander Center. Dr. Jerolleman is one of the founders of the Natural Hazard Mitigation Association (NHMA) and served as its Executive Director for its first seven years. Alessandra is a subject matter expert in climate adaptation, hazard mitigation, disaster recovery and resilience with a long history of working in the public, private and nonprofit sectors. Dr. Jerolleman speaks on many topics including: hazard mitigation and climate change; campus planning; threat, hazard and vulnerability assessments; hazard mitigation planning; protecting children in disasters; justice in disaster recovery; and public/private partnerships.

If you enjoy this interview, don’t miss Alessandra’s previous presentation to FAC Net on recovery through the lens of justice (available here!).

Tell us a little bit about yourself:

Alessandra: I am an associate professor of Emergency Management at Jacksonville State University. I also do a lot of work with small community organizations like the Lowlander Center, which is an applied research center that’s primarily indigenous-led in coastal Louisiana and the First Peoples Conservation Council. Much of my work focuses on disaster recovery and, in particular, its nexus with justice and equity. The vast majority of my work is done in partnership with communities. I’m a firm believer in applied research, participatory action research and working with people and communities towards their goals and their objectives– particularly when they’re in situations where many of our systems don’t really have the ability to meet their needs.

What led you to recovery?

Alessandra: Certainly seeing disasters play out over my lifetime has had an impact on my path but to be honest, when I first started my professional career I was very interested in the nonprofit sector. In particular, I was interested in issues for children and families, but living in the Greater New Orleans area you can’t really separate children and families from the bigger questions around disaster recovery and disaster resilience. Hurricane Katrina, in particular, really brought this home for me and altered my path. In the last 15 years or so, it is just so very clear that not only are disasters increasing in frequency and severity but the impacts are really disparate from one group to another. We’re creating these deeply entrenched cycles of vulnerability. After a while you can’t look away as it feels like such a pressing need.

The downed tree blocking off access to Alessandra’s street in New Orleans right after Hurricane Ida. Photo by author.

How do you think about recovery and what recovery means?

Alessandra: I think that we need to stop thinking so much about recovery as a discrete thing that starts and ends. We are dealing with this right now, where we have multiple stressors (climate, fire, COVID, flooding, hurricanes) one on top of the other. Depending on where you are in the country, you may have questions around the economy or concerns about the future for your children. We have this convergence of all of these events at once, and they’re interconnected, and yet when we think about recovery we have this tendency to say “Recovery is focused on this event that just happened” and we tend to define it as “People get their houses back, we make some repairs to infrastructure, we restore some of the natural environment and we are done.” We don’t realize that recovery takes decades– there are intergenerational impacts from the Dust Bowl that are still felt today. It’s almost as if the disaster cycle has collapsed. You’ve got areas recovering from last year’s fires and worrying about new ones all at the same time. Some of these areas also have long histories of housing pressures, health disparities and limited food access – all weighing on families at once.

The other thing that I think is important to call out is the assumption that it’s great to think and talk about equity, but only when we have the bandwidth for it. People tend to think “when there’s an emergency, when people’s lives are on the line, we are just going to save as many people as we can because that’s the greater good.” However, that’s a very instrumentalist argument and I think it puts us in a dangerous place where we essentially only think about things like equity when it’s easy, and as a result don’t get beyond lip service.

The Entergy outage map after Hurricane Ida with red marking the outages. Screenshot courtesy of the author via Entergy New Orleans.

One of the more significant conversations happening in the wildfire world right now has to do with how we create maps which integrate social vulnerability. These maps have significant implications for equity and I would love to hear more about your thoughts in this area.

Alessandra: On the one hand, when you’re looking at the big picture, across the country or across counties in a state, it can be useful to understand where there are greater concentrations of certain factors that we know often correlate to vulnerability or correlate with less of an ability to be prepared and recover. This is not a personal failing, it’s about the systems. Where we know, for example, we have a lot of agricultural workers living in very unsafe, substandard housing because their employers aren’t providing anything else and we don’t have good legal protections for them, we also know that we need to be additionally concerned that in the event of a fire, that population is more likely to experience adverse outcomes and less likely to access help. So, there is some value to taking that step back and understanding the context.

The problem is that we are then asked to make these very normative judgments about who needs help, who needs more help, and why they need more help. Although these kinds of questions can look value neutral, they are not. To understand, we have to look at who’s defined as vulnerable, who’s defined as deserving, and what the data sources are. For example, many of these data models are using census data. Census data doesn’t count undocumented persons and it substantially undercounts transitory populations and undercounts on tribal reservations. There is a danger with all of these technocratic solutions that we take something that is somewhat useful for a relative lens on a really large scale and we decide that it’s useful at the scale of a neighborhood block. Or even worse, that we decide that it is the only scientifically appropriate way to drive decisions around resource allocation.

It makes people deeply uncomfortable to think that they might be asked to distribute resources disparately. It feels uncomfortable to tell a professional if you only have 100 of X, you need to give 90 to this single place. It feels like you’re asking to discriminate in the name of not discriminating. Of course, this denies the long history of entrenched discrimination that created disparate needs in the first place, and the fact that uneven distribution of resources has long characterized our society – just in the other direction. As a result, these indices and maps feel safer, less emotional, and more scientific – even when professionals understand and acknowledge the data limitations (which is not always the case).

Measuring progress, and the way we establish that local needs are being met, can be challenging. I am wondering if you have insights on how we move forward with metrics?

Alessandra: I think our path forward isn’t to do away with metrics, but rather to put them in their place. We can start with the bigger picture in which we can use more quantitative metrics but then you need local relationships. Some of these coastal communities that I’ve been working with can provide a great example. If you talk to the pastor of the small African American church that has about 100 people in his congregation, he knows exactly what people need. He knows Miss So-And-So is diabetic and needs this, Mr. So-And-So, he’s going to tell you that he doesn’t need any help, but he had a stroke three years ago and somebody really should help and put his fence back up. That is not data present in the census, but it’s qualitative data that is based on relationships. From a bigger funding perspective, we need to get over worrying that we’re going to get swindled out of 1% of the cost of a fighter jet and just trust the people that are on the ground to do the right thing the vast majority of the time. These people know their communities and they are in the best position to render help. This means we have to accept that, sometimes, it may mean that money isn’t spent perfectly but on the whole, it’s going to lead to better results.

A house that some volunteers and Alessandra floodproofed in Baton Rouge after the 2016 flooding (in process photo shows the technique). Photo by the author.

We don’t bat an eye at crazy levels of overhead, at insane rates for person-hours, for these huge private sector contractor contracts that get let out in response and recovery. But you see, for example, after Hurricane Sandy the Office of Inspector General report out of New York State found instances where some contractors accidentally double invoiced and got a few extra hundred thousand dollars. It was an accounting error and the world moved on. Yet, if you have one person who mistypes how much they received in insurance and ends up with an extra $100 from a federal agency they are threatened with lawsuits. If the large company gets a letter, their attorneys are more than capable of dealing with it. The older person, on fixed income, doesn’t know what to do and it costs them time and stress. Yet, it probably cost the government more to pay a contractor to send her the letter and recover the funds, than the extra payment she received. I think we have a double standard that comes back to the idea that people have to show that they are deserving people. We have these very weird double standards about who has to get held accountable, and why.

Do you have a vision for what the future should look like?

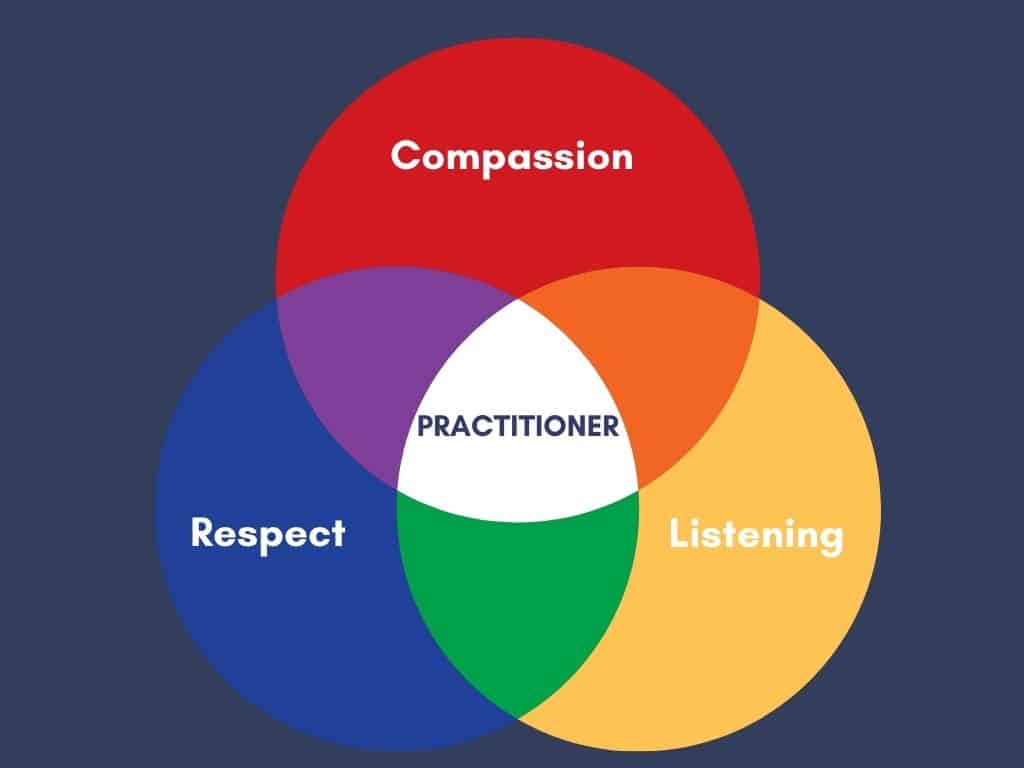

Alessandra: It has always been very apparent to me that our solutions have to come from a place of compassion, respect and listening. And our solutions can’t be imposed by technocratic experts. My PhD is useless if I’m trying to go down the bayou in a pirogue [long, narrow wooden shallow boat] or help with brush clearing. There are a lot of things I just can’t do! So, we have to really listen to people with deep histories, living in communities that have been working with the environment in adaptive management. If we don’t learn how to really listen we are not going to succeed.

The interaction between compassion, respect and listening is not sequential but instead interconnected. Alone, none are enough. The practitioner, shown in the center of the diagram, brings their whole self to the work, affect included. Graphic by the author.

We also, collectively and right now, need to figure out how to get beyond the need to assign levels of deservedness to different people in different circumstances. The truth is we are all deeply interconnected. COVID-19 shows us this with supply lines (it was impossible to get toilet paper)! Any one individual’s particular set of circumstances, situation or choices, is embedded in these broader systems that in many cases have been systems of oppression dating back to colonialism. Because our systems often render some people invisible, it gets very easy to assume that people who appear to be taking more proactive steps are therefore more deserving of help.I think we need to figure out how to address that if we’re really going to move the needle in recovery.

Recovery can be an emotionally challenging space in which to work. What advice do you have for practitioners?

Alessandra: I have seen so many practitioners burn themselves out. We professionalize ourselves out of our humanity– it is a very Western context to think that we have to be dispassionate and that this dispassion is the right way to work. But these practitioners in your network, they’re not just working on fire in an abstract way. Fire is impacting their homes, their families, the people they care about, even the places they’ve grown up. When you have indigenous people the impacts may be to the natural environments, the places that they consider sacred and to which they are deeply connected. This work is emotional, and I think we do ourselves a disservice if we try to be dispassionate. You can be a professional and still recognize your thoughts, your feelings and your emotions. If you do, you’re less likely to burn out. We burn through people in response, we burn through people in recovery, and we leave them behind deeply traumatized.

Hurricane Ida can provide an example of this. There are coastal communities that are decimated. These are people that I know deeply, that taught my daughter how to fish. I’ve spent almost 20 years going down there and so much is gone. It breaks my heart and brings tears to my eyes. I think we have to sometimes say that it is okay to grieve, it is okay to be human, because part of our problem right now is that we have forgotten how to be human with each other.

How can practitioners start bringing a more equitable and just lens to their work?

Alessandra: That’s one of the questions that keeps me up at night. One of the things we always can do, and maybe don’t do enough, is to render this work visible. I think we often have mismatches between what we, collectively as a nation or as organizations, believe our values are and what we’re actually producing. I went to a required training course years ago where they said one thing that really stuck with me: we don’t always look to see where our time and our attention goes relative to what we say we care about. It struck me later as a single mom, if I were to make a list of what I care about, the thing that most matters to me is my child. Yet, it is so easy to turn down a dozen opportunities to engage with her because I needed to do this or I needed to do that. Some of those trade offs are inevitable, but there are choices that we make. At some point we have to ask ourselves if we are actually living the way we think we are living. Are we putting our time and our energy where we think we are or are we not?

Making time for the thing that matters most and the most representative photo of Alessandra’s whole self, playing in the rain with her daughter Catalina. Photo by Author.

We sometimes are upset at what our laws and policies let us do or don’t let us do. But we rarely take the time to analyze them. There’s a range of things that we can do with discretion. There are things we obviously can’t do, but there is operating space where we do have some discretion. If we’re going to embody our values, we need to be using that discretion to the fullest extent to support those values. Ultimately, we’re going to hit the wall where we can go no further. Then we work with advocates and activists to shift that wall. That is an option too, but we have to be doing both.

* * * *

Thank you SO much, Dr Jerolleman, for this wonderful interview. I very much appreciate you taking the time to share your insights and experiences with us. Thank you!

This is a lovely piece, and so relevant. Thank you for sharing your thoughts, Alessandra!

This is a fantastic commentary, thank you so much to Dr. Jerolleman and FAC Net folks. I want to share this on my Facebook as well as share it with my daughter who has a therapy practice and is well informed about the challenges discussed in this essay. As in the past, I will ask permission to share this, wait until I hear back from somebody before posting. Thank you for another excellent writing/interview.

Hi Terry! You are always welcome to share links to the blogs on our website on your social media and other channels! We only request people ask permission when they want to re-publish (meaning re-produce in a new format on their own website or other channel). Please share away! Thanks for checking in!

This is a fantastic article! Thank you for sharing.

Wonderful piece. Thank you Dr. Jerolleman and FAC folks for a very insightful, heartfelt piece. Definitely will share.

This is so true for me here in Kamloops, BC, Canada. We have been through wildfires, floods and residential school trauma as well as personal traumatic events with the deaths of friends and family members all in one year. As a contractor at ground zero of 2017 wildfires, I was paid well, but at the expense of my mental, emotional and physical health (and I thought this is such a crazy setup funded through FEMA). So, I decided to focus more on teaching with my husband and addressing practical local solutions to improve the well-being of those around us. Still, this year I have found myself exhausted and easily angered. My goal for 2022 is inner peace and to support people in small tangible ways. We have so many storied lessons across the ages that speak to this as a way of knowing and a way of thriving in and for our communities.