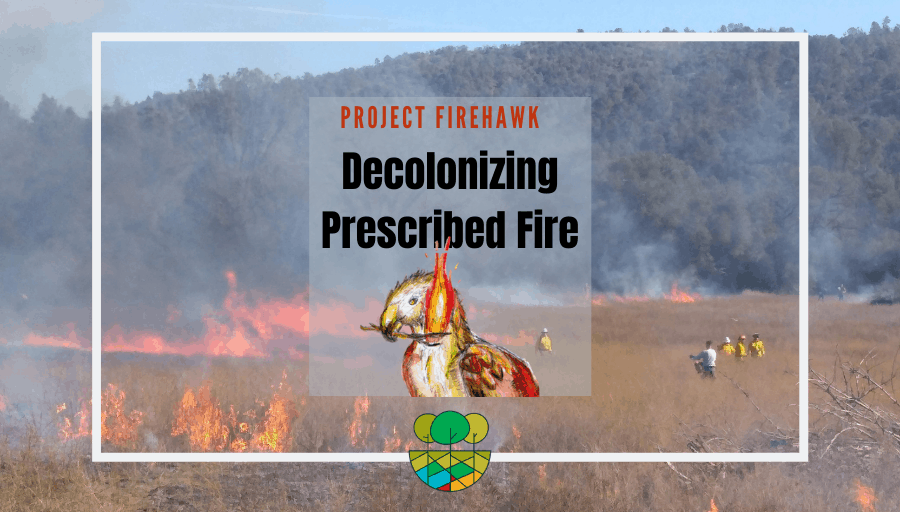

Photo Credit: Cultural burn at an 8,000 year-old Miwok village site led by North Fork Mono elder Ron Goode and his family. Photo by Chris Adlam.

Editors’ Note: This blog is another installment in our Project Firehawk series, the series is named in reference to a cohort of Australian birds who carry fire in their beaks to spark change. Its essays explore the core underpinnings of our work, and in some cases, challenge the status quo. The series’ authors are bold as they tackle hard questions to reveal needed shifts in our relationship with fire. We all must be unafraid as we investigate what is (and isn’t) working in our current system. These thought pieces may challenge you, create controversy, or even cause you to stand up and cheer. Regardless of your reaction, we hope this series causes you to pause and maybe even initiate a larger conversation about what it really means to live better with fire.

This blog, written by Christopher Adlam, Regional Fire Specialist at Oregon State University Extension Fire Program and Deniss Martinez, PhD Candidate in Ecology at the University of California, Davis focuses on traditional and Indigenous fire practices. Here they get really honest about the impacts to Indigenous people from the colonization of their lands and their fire practices, as well as share a wealth of thought provoking articles and research.

* * * *

Author Christopher Adlam

Christopher recently completed his PhD in ecology at UC Davis, during which he worked with Indigenous communities across northern California on the revitalization

of cultural burning practices and Indigenous-led collaborative landscape management. He believes that community-based, intercultural fire governance is a key part of solving the fire crisis.

Author Deniss Martinez

In addition to her PhD research in ecology Deniss is also a Health Policy Research Scholar with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Her work seeks to understand how California Native Nations navigate power differentials in natural resource stewardship collaborations. Her research addresses questions of Indigenous science, environmental justice, and governance.

* * * *

This past year has brought to light the many ways in which institutions and social norms uphold white supremacist ideologies. We have seen statues topple and institutions held accountable, but it’s also important to understand how white supremacy is scarred on the land, beginning with the displacement of Indigenous people and the criminalization of their traditional burning practices. Indigenous cultures across North America are dependent on fire, which they use to increase the abundance of plant and animal resources, maintain travel routes and gathering areas, and for many other material, social, and spiritual purposes. Since colonization, Indigenous fire practices have been suppressed, often violently, for motives that run deeper than mere ignorance of fire’s benefits or fear of its destructive potential.

Fire suppression: a pillar of colonization

In the 19th century, a central legal and moral argument justifying taking land from Native peoples was that they didn’t use it, and therefore they didn’t own it. For example, British Columbia’s Indian reserve commissioner, Gilbert Sproat, asserted in 1868 that “any right in the soil which these natives had as occupiers was partial and imperfect as, with the exception of hunting animals in the forest, plucking wild fruits and cutting a few trees . . . the natives did not in any civilized sense, occupy the land.” For this argument to work, Indigenous land management, and particularly the use of fire, needed to be dismissed and maligned. Fire suppression became a pillar of colonization, used to subdue tribes and extinguish their claims to the land. In California, Governor Arrillaga mandated Spanish missionaries to punish “childish” Indians for setting fires in 1793. This prohibition was renewed by the state of California in 1850, in the same act that allowed for the enslavement of Native Americans. People who sought to maintain traditional burning practices were beaten, jailed or shot well into the 20th century (in a letter from 1918, Forest Service district ranger F. W. Harley recommended that “renegade” Indians who “set fires for pure cussedness” should be shot “like coyotes”). Little by little these practices dwindled, surviving only thanks to the resilience and tenacity of a few practitioners.

From suppression to…appropriation?

Today, Indigenous people in many cases still endure the effects of fire suppression, including the decline in traditional foods and the resulting impacts to their health and well-being, vulnerability to high-severity wildfires, and continued inability to fulfill their traditional stewardship obligations. The fires that burned across the West in August and September 2020 have prompted deeper reflections about the damage caused by the removal of Indigenous burning, while at the same time starkly illustrating the vulnerability of Tribal communities and cultural resources.

However, while the direct impacts of fire suppression on Indigenous communities deserve greater awareness, there is also a second, more subtle way that non-Native fire management can perpetuate the erasure of Indigenous land stewardship: appropriation of Indigenous cultural fire practices. It is now obvious that aggressive fire suppression has deep ecological and social costs, and in response, non-Native land managers, conservationists, and researchers have espoused the use of prescribed fire to reduce fuels, combat biodiversity loss and promote forest health. This shift is leading to improvements in land management. However, we must also ask: how does this adoption of an Indigenous practice by non-Indigenous people play into the colonial violence perpetrated by fire suppression? How do we make sure that current efforts do not continue the pattern of Indigenous erasure and instead acknowledge and uplift prescribed burning’s intellectual and cultural origins?

Diana Almendariz (Wintun/Maidu cultural practitioner) instructs UC Davis students in the burning of deergrass, a traditional basketry plant, Cache Creek Conservancy, Woodland, CA, 2019. Photo by Christopher Adlam.

Tribal leadership in prescribed fire deserves acknowledgement

To answer these questions, we must first recognize the advocacy and leadership of tribes and Tribal fire practitioners. At the same time that non-Native land managers are coming to realize the benefits of fire, tribes across the continent are revitalizing the use of cultural burning and seeking to manage their ancestral homelands in ways that are consistent with their priorities and values. Their efforts are leading to increased cross-boundary forest restoration, improvements to prescribed burning techniques, and forward-looking planning, particularly in regard to climate change adaptation. This momentum is the product of decades-long organizing and deliberation. Tribal fire departments now support agencies in implementing prescribed burns, while Indigenous researchers are developing cross-disciplinary and cross-cultural insights on fire ecology and land management, health and social action. Practitioners are demonstrating their fire knowledge to educate managers, policymakers, and regulators. They are pushing for reforms to fire management that will enable more prescribed burning, while mobilizing momentum and public support for this practice. This leadership stands to improve the health and well-being of Tribal communities, improve conservation outcomes, and support the work of all prescribed fire practitioners.

This is why acknowledging prescribed burning as an Indigenous practice is more than a polite gesture. It is giving credit and respect to the hard work of contemporary practitioners, as well as past generations who fought to maintain this body of knowledge. Many fire researchers and professionals seem comfortable acknowledging the historical role of Indigenous burning and will mention it in their publications and management plans. However, this is not always done, or it is done in the past tense, or as a symbolic footnote. This is not enough.

Indigenous perspectives and fire knowledge are too often downplayed or ignored, impacting Native fire practitioners. Indigenous students and researchers in academia, and Tribal members working in government agencies still struggle with lack of visibility, and work environments that devalue their cultural heritage. Indigenous firefighters must endure their knowledge being ignored and subjugated to Western fire suppression tactics. These patterns continue to erode Indigenous peoples’ role in fire management. Non-Native fire practitioners must work to counter this trend by uplifting the perspectives and struggles of the original fire stewards of these lands. In this way, they can work against the erasure of the very practices and knowledge they are now embracing, rather than contributing to it.

Basketweavers and cultural practitioners demonstrate burning of deergrass and redbud at an Indigenous Fire Workshop; Tending and Gathering Garden, Cache Creek Conservancy, Woodland, CA, 2019. Photo by Christopher Adlam.

Supporting and uplifting Indigenous fire management

Indigenous fire practitioners are continuing to shape fire management from policy to practice, and this work deserves more than simple acknowledgement. Non-Native prescribed fire practitioners at all levels and in all sectors must endeavor to tangibly support this work. This can take on many forms: NGOs can lend organizational capacity to Tribal-led efforts, or collaboratively apply for grants that support them. Land trusts, conservation groups, and public land managers can secure access to land and cultural resources, for example by designing “cultural management areas” where cultural burns can take place. Universities can support community-based research that values Indigenous perspectives and control over the knowledge-building process. Prescribed fire trainings can provide scholarships to Indigenous participants, and include cultural exchanges led by traditional knowledge holders. Cooperative Extension specialists can plan for Tribal outreach that includes information about regulations and services relevant to cultural burning. Government agencies can collaborate with tribes over the management of their ancestral lands.

Decolonizing prescribed fire means to actively support the leadership of tribes in fire management and to foster the renewal of cultural burning practices. If we fail to meaningfully engage in this task by ignoring the connections between Indigenous cultures and fire ecology and practice, we will perpetuate the colonial, white supremacist violence that has sought to eliminate Native Americans and their fire knowledge from the landscape. It’s time to heal the scars of white supremacy, which run deep on the land as they do in society. This work begins by decolonizing prescribed fire and re-centering Indigenous knowledge and leadership in order to move towards a more just fire management paradigm.

Author Deniss Martinez enjoys a good laugh with Ron Goode, Tribal Chairman of the North Fork Mono, at a cultural burn near Mariposa, CA, 2017. Photo by Zack Emerson.

* * * *

Please note that comments are manually approved by a website administrator and may take some time to appear.

Thank you for this thoughtful piece, Chris and Deniss. I specifically love the calls to action at the end. I look forward to diving in to all of the articles, videos and resources you shared in the hyperlinks!

Thanks for this thoughtful and well written article. I especially appreciate the inclusion of actionable items folks can take. This article really helps broaden my understanding of the history of fire management.

Delighted to see this well-researched, absorbing commentary on our current climate emergency situation. This will help things change as quickly as necessary to slow down the increase in wildfires throughout California and beyond. Indigenous leadership — yes! Unlearning our colonized ways of thinking — yes! Thank you for these excellent guidelines. We will be contacting you in the near future to describe what Ecosystem Restoration Camp Communities in California are trying to do as our Cultural Competence Circle encourages personal commitments to education and action.

A huge thank you for this blog, it really made me take a moment to reflect on how we can move forward with fire practices in a more inclusive manner. The links and resources you provided gave me a great opportunity to dig even deeper.

Thank you for this great article and resources.

Thank you, and thanks for the feedback!

Yay! Thanks for this yall. May every After Action Review following white-led prescribed fire include a question of ‘how did we work to subvert and dismantle white supremacy in fire today?’ how about following a fire fight too?

Excellent piece. I very much appreciate the rigor and perspective. I’ll be using this as a reference for years to come!

Thank you for sharing the history and importance of prescribed fire and Indigenous wisdom. The solutions and envisioning in the last part of the article was particularly inspiring.